Quick Start Guide

TL;DR

You can find a demonstration notebook here.

This guide will follow the steps necessary to get from model parsing to simulation.

We will use a pre-defined config file (accessible in the repository) "MODELS/POST82.yaml".

Reading Model Configuration

The configuration files are parsed by the SymbolicDSGE.ModelParser class.

The class provides a .get() method to return a ModelConfig object.

from SymbolicDSGE import ModelParser

from sympy import Matrix

from warnings import simplefilter, catch_warnings

model = ModelParser("MODELS/POST82.yaml").get()

with catch_warnings(): # (1)!

simplefilter(action="ignore")

mat = Matrix(model.equations.model)

mat

- Wrapping equations in a

sp.Matrixis deprecated and used here solely for pretty-printing.

We've read the config and displayed the equations in a matrix:

We can see that all variables are converted to SymPy objects (symbols/functions) and are accessible through the ModelConfig interface.

Compilation

In compilation, the symbolic model is projected into a functionalized and completely numeric form. Time-dependent variables are separated and equations are written as lambda objectives. Finally, the solver backend linearsolver is exposed to a single function representing all model equations.

from SymbolicDSGE import DSGESolver

solver = DSGESolver(model)

compiled = solver.compile(

variable_order=None, # (1)!

params_order=None, # (2)!

n_state=3, # (3)!

n_exog=2, # (4)!

)

print("Equations with symbols removed: \n", "\n".join(map(str, compiled.objective_eqs)))

print("\n")

print("Equations as passed to the solver: \n", compiled.equations)

None | list[Function].Noneuses the order in the config file.None | list[str].Noneuses the order in the config file.- Number of state variables (must be supplied)

- Number of exogenous variables (must be supplied)

At compilation, the equations are transformed as shown in the code output:

Equations with symbols removed:

-beta*fwd_Pi + cur_Pi - cur_x*kappa - cur_z

-cur_g + cur_x - fwd_x + tau_inv*(cur_r - fwd_Pi)

-cur_r*rho_r - e_R + fwd_r + (rho_r - 1)*(fwd_Pi*psi_pi + fwd_x*psi_x)

-cur_g*rho_g - e_g + fwd_g

-cur_z*rho_z - e_z + fwd_z

Equations as passed to the solver:

<function DSGESolver.compile.<locals>.equations at 0x0000012D16AB5B20>

Variable Placement

The solver relies on the exogenous variables being placed in the first indices. You should ensure the first n_exog entries of the order correctly map to the exogenous variables. (either through the config or via the ordering)

Solution

The solution step takes steady-state values and optionally parameter calibrations to provide a SolvedModel.

from numpy import float64, array

sol = solver.solve(

compiled,

parameters=None, # (1)!

steady_state=array([0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], dtype=float64),

log_linear=False,

)

print("Is stable: ", sol.policy.stab == 0) # (2)!

print("Eigenvalues: ", sol.policy.eig)

None | dict[str, float].Noneuses the values inModelConfig.calibration- stable if

sol.policy.stab == 0

- Complex numbers are an artifact of

linearsolve. All relevant matrices are cast to reals withnp.real_if_close

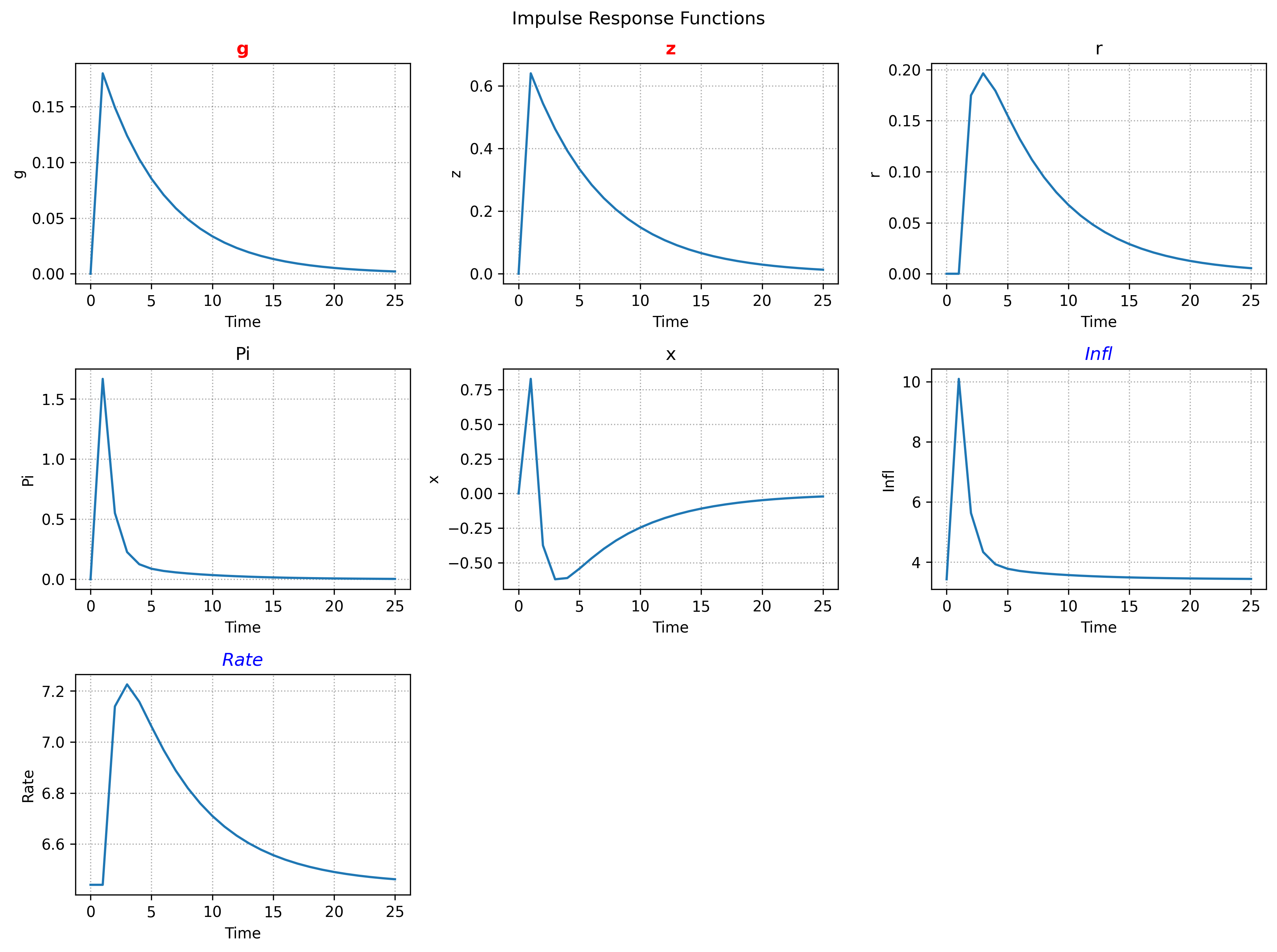

Inspecting Model Dynamics

While we can check the matrices directly, we can also use the built-in methods SolvedModel.irf and SolvedModel.transition_plot to display the dynamics.

irf_dict = sol.irf(

T=25,

shocks=["g", "z"],

scale=1.0, # (1)!

observables=True, # (2)!

)

sol.transition_plot(

T=25,

shocks=["g", "z"],

scale=1.0,

observables=True,

)

irf_dict["z"] # (3)!

shock = sig_var * scale- Include observables in output.

- Path of the variable

z.

This produces the outputs:

array([0. , 0.64 , 0.54399995, 0.46239991, 0.39303989,

0.33408388, 0.28397127, 0.24137556, 0.2051692 , 0.17439381,

0.14823472, 0.1259995 , 0.10709957, 0.09103462, 0.07737942,

0.0657725 , 0.05590662, 0.04752063, 0.04039253, 0.03433365,

0.0291836 , 0.02480605, 0.02108514, 0.01792237, 0.01523401,

0.01294891])

Simulation

SolvedModel also supplies a .sim() method for simulations.

The method simulates T steps given an initial state array and a shock specification.

Shock specifications can take two basic forms.

- A callable returning the complete shock array:

Callable[[float | ndarray], ndarray] - A

np.ndarrayof innovations

Either specification is delivered to .sim in a dictionary corresponding to the variable the innovations are meant to effect.

In case of multiple shocks with correlation the key for the dictionary uses "g,z" syntax. In correlated cases, the Callable option input should take a covariance matrix while the array option must be of shape (T, n_correlated_shocks). (order should match the dictionary key)

SymbolicDSGE.Shock is an interface simplifying the shock generation process. It can produce Callable generators for both univariate and multivariate shocks. The class has support for all SciPy distributions from the rv_generic and multi_rv_generic hierarchies. Alongside SciPy support, custom distributions implementing the .rvs method are supported through the pass-through of distribution args/kwargs.

from SymbolicDSGE import Shock

T = 200

shock_gen = lambda seed: Shock( # (1)!

T=T,

dist="norm",

multivar=True,

seed=seed, # (2)!

dist_kwargs={ # (3)!

"mean": [0.0, 0.0],

},

).shock_generator() # (4)!

sim_shocks = {

"g,z": shock_gen(seed=1) # (5)!

}

- Notice the seed argument to the class being parametrized through a lambda. This step is not necessary for functionality. It saves the code of declaring two instances with different seeds if two shocks share distributions.

- Seed is passed through here, the code below would operate the same if we used

seed=1instead of using a lambda. - The

kwargsspecified here are passed to the distribution object in the backend (toSciPy'srvsmethods in this case) shock_generatorproduces theCallableobject from the parameters given at class initialization. The methods either accept a floatsigor a covariance matrixcovcreated inside the.simmethod.- The value in this pair is a standalone function that does not depend on model parameters. Once created it can be reused across simulations; the appropriate

sigorcovis constructed internally from model parameters at simulation time.

shock_gen() returns a callable that .sim uses in the simulation loop to produce shocks. With the shocks produced, we can simulate stochastic paths as follows:

import pandas as pd

sim_data = sol.sim(

T=T,

x0=array([0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], dtype=float64), # (1)!

shocks=sim_shocks,

shock_scale=1.0,

observables=True,

)

del sim_data["_X"] # (2)!

pd.DataFrame(sim_data).head(10)

- Simulation starts at steady state

"_X"is andarrayof all non-observable states for each time t. It is deleted here for code brevity in producing aDataFrame.

| g | z | r | Pi | x | Infl | Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.43 | 6.44 |

| 1 | 0.0113 | 1.0502 | 0 | 2.0097 | 0.4527 | 11.469 | 6.44 |

| 2 | -0.2055 | 0.5741 | 0.205 | -0.4441 | -1.6807 | 1.6538 | 7.2601 |

| 3 | -0.4925 | 1.0832 | 0.1083 | 0.2587 | -1.8046 | 4.4646 | 6.873 |

| 4 | -0.4139 | 2.0507 | 0.0962 | 2.3427 | -1.0963 | 12.8009 | 6.8249 |

| 5 | -0.3628 | 1.9517 | 0.3014 | 1.2818 | -2.2254 | 8.557 | 7.6456 |

| 6 | -0.5415 | 2.6315 | 0.3544 | 1.8491 | -2.8505 | 10.8264 | 7.8577 |

| 7 | -0.5357 | 2.0374 | 0.4482 | 0.2843 | -3.6404 | 4.5671 | 8.233 |

| 8 | -0.5484 | 2.477 | 0.362 | 1.503 | -2.9801 | 9.442 | 7.8881 |

| 9 | -0.6129 | 2.0109 | 0.4187 | 0.1822 | -3.7172 | 4.1587 | 8.1148 |

Alternative to a DataFrame, we can also plot the simulated paths:

from numpy import ceil, sqrt

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig_square = ceil(sqrt(len(sim_data))).astype(int)

size = (4 * fig_square, 3 * fig_square)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(fig_square, fig_square, figsize=size)

ax = ax.flatten()

while len(ax) > len(sim_data):

fig.delaxes(ax[-1])

ax = ax[:-1]

for i, (var, path) in enumerate(sim_data.items()):

ax[i].plot(path)

ax[i].set_title(var)

ax[i].grid(linestyle=":")

plt.suptitle(f"Simulation over {T} periods with stochastic shocks", fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout()

Further Steps

This guide covers the basic capabilities and usage of SymbolicDSGE. Further tools include:

SymbolicDSGE.FREDfor easy U.S. macro data retrievalSymbolicDSGE.math_utilsfor basic detrending, HP filters, etc.SymbolicDSGE.KalmanFilterfor a one-sided Kalman Filter implementation. (standalone as of now but easy model integration interface will be developed)

If you've read to this point and would like to inspect/interact with the code this guide refers to, you can visit this link to the file.